Во всех экономиках наблюдается некоторый уровень инфляции, который возникает, когда средняя цена товаров увеличивается по мере снижения покупательной способности этой валюты. Обычно правительство и финансовые институты работают вместе, чтобы инфляция происходила плавно и постепенно. Однако в истории было много случаев, когда темп развития инфляции ускорился до такой беспрецедентной степени, что это привело к снижению реальной стоимости валюты этой страны в угрожающих масштабах. Этот ускоренный уровень инфляции является тем, что мы называем гиперинфляцией.

В своей книге «Монетарная динамика гиперинфляции» экономист Филип Кейган заявляет, что период гиперинфляции начинается, когда цена товаров и услуг увеличивается более чем на 50% в течение одного месяца. Например, если цена мешка риса вырастет с 10 до 15 долларов менее чем за 30 дней, а с 15 до 22,5 долларов к концу следующего месяца, это будет гиперинфляция. И если эта тенденция сохранится, цена на мешок риса может вырасти до 114 долларов за шесть месяцев и более 1000 долларов за год.

Редкостью является уровень гиперинфляции когда он остается неизменным на уровне 50%. В большинстве случаев она ускоряется настолько быстро, что цены на различные товары и услуги могут резко возрастать в течение одного дня или даже часов. В результате роста цен, доверие потребителей снижается, а стоимость государственной валюты уменьшается. В конце концов, гиперинфляция вызывает своеобразный эффект волны, приводящий к закрытию компаний, росту уровня безработицы и к снижению поступления налогов. Хорошо известные эпизоды гиперинфляции произошли в Германии, Венесуэле и Зимбабве, но многие другие страны также столкнулись с подобным кризисом, включая Венгрию, Югославию, Грецию и многие другие.

Гиперинфляция в Германии

Один из самых известных примеров гиперинфляции имел место в Веймарской Республике Германии после Первой мировой войны. Германия заимствовала огромные суммы денег для финансирования военных действий, полностью полагая, что они выиграют войну и использовали репарации от союзников для погашения этих долгов. Германия не только не выиграла войну, но и должна была заплатить миллиарды долларов в качестве компенсации.

Несмотря на различные дискуссии о причинах гиперинфляции в Германии, некоторые из наиболее часто упоминаемых причин включают в себя: приостановление действия золотого стандарта, военные репарации и безрассудный выпуск бумажных денег. Решение приостановить золотой стандарт в начале войны означало, что количество денег в обращении не имело отношения к стоимости золота, которым владела страна. Этот спорный шаг привел к девальвации немецкой валюты, которая вынудила союзников требовать выплаты репараций в любой валюте, кроме немецкой бумажной марки. В ответ Германия напечатала огромные суммы собственных денег на покупку иностранной валюты, в результате чего стоимость немецкой марки обесценилась еще больше.

В некоторые моменты этого эпизода темпы инфляции росли со скоростью более 20% в день. Немецкая валюта стала настолько бесполезной, что некоторые граждане жгли бумажные деньги, чтобы согреть свои дома, поскольку это было дешевле, чем покупать дрова.

Гиперинфляция в Венесуэле

Благодаря своим большим запасам нефти Венесуэла поддерживала здоровье экономики в течение 20-го века, но избыток нефти в 1980-х годах, сопровождаемый неэффективным управлением и коррупцией в начале 21-го века, привел к сильному социально-экономическому и политическому кризису. Кризис начался в 2010 году и сейчас является одним из самых сильнейших в истории человечества.

Уровень инфляции в Венесуэле стремительно развивался, увеличившись с годового уровня в 69% в 2014 году до 181% в 2015 году. Период гиперинфляции начался в 2016 году, отметив 800% -ную инфляцию к концу года, затем 4000% в 2017 году и более 2 600 000% в начале 2019 года.

В 2018 году президент Николас Мадуро объявил, что для борьбы с гиперинфляцией будет выпущена новая валюта (суверенный боливар), которая заменит существующий боливар в размере 1/100 000. Таким образом, 100 000 боливаров стали 1 суверенным боливаром. Однако эффективность такого подхода весьма сомнительна. Экономист Стив Ханке заявил, что сокращение нулей - это «косметическое изменение» и «оно ни на что не влияет, пока экономическая политика остается прежней».

Гиперинфляция в Зимбабве

После обретения независимости в 1980 году экономика Зимбабве в первые годы была достаточно стабильной. Однако правительство президента Роберта Мугабе в 1991 году инициировало программу ESAP (Программа структурной перестройки экономики), которая считается основной причиной экономического коллапса Зимбабве. Наряду с ESAP земельные реформы, проведенные властями, привели к резкому сокращению производства продуктов питания, что привело к большому финансовому и социальному кризису.

Доллар Зимбабве (ZWN) начал подавать сигналы о нестабильности в конце 1990-х годов, а гиперинфляция начались в начале 2000-х годов. Годовой уровень инфляции достиг 624% в 2004 году, 1730% в 2006 году и 231 150 888% в июле 2008 года. Из-за отсутствия данных, представленных центральным банком страны, ставки после июля были основаны на теоретических оценках.

Согласно подсчетам профессора Стива Х. Ханке, гиперинфляция в Зимбабве достигла пика в ноябре 2008 года при годовом показателе 89,7 секстиллионов, что эквивалентно 79,6 млрд процентов в месяц или 98% в день.

Зимбабве была первой страной, которая испытала гиперинфляцию в 21-м веке и зарегистрировала второй худший инфляционный эпизод в истории (после Венгрии). В 2008 году ZWN был официально оставлен, а иностранные валюты были приняты в качестве законного платежного средства.

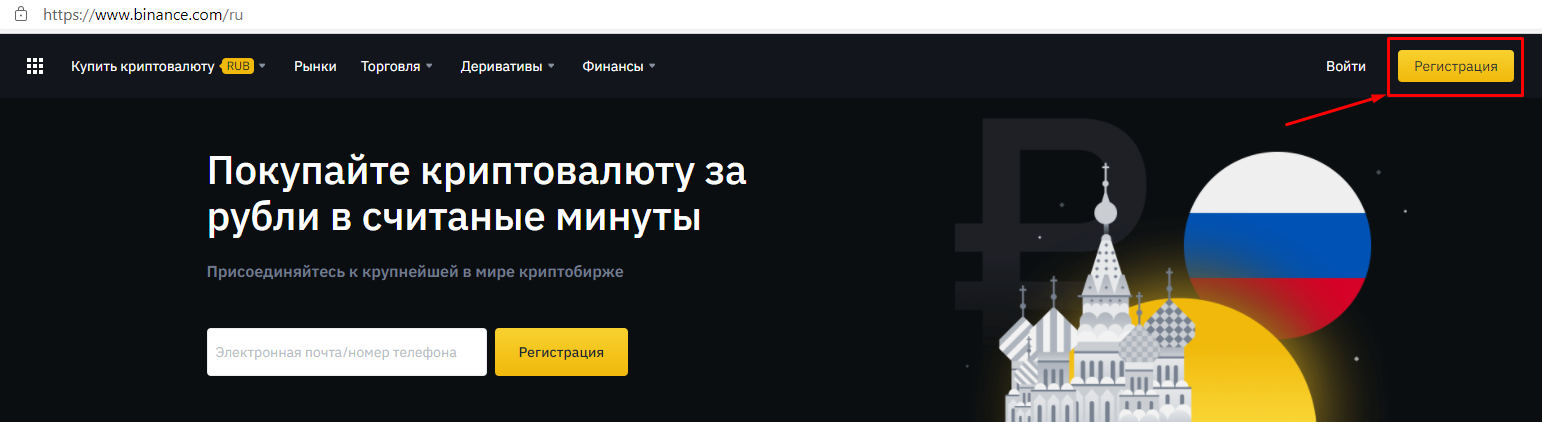

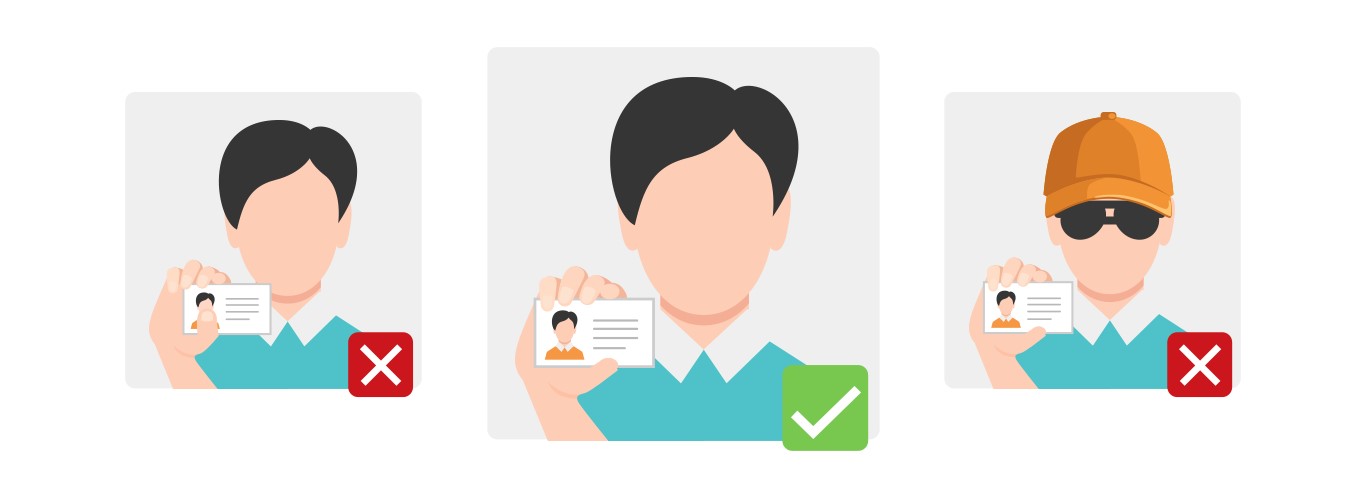

Использование криптовалют

Поскольку Биткойн и другие криптовалюты не основаны на централизованных системах, их ценность не может быть определена государственными или финансовыми учреждениями. Технология Blockchain гарантирует, что выпуск новых монет происходит по заранее установленному графику, а каждая единица уникальна и не подвержена дублированию.

Вот некоторые из причин, почему криптовалюты становятся все более популярными, особенно в странах, которые имеют дело с гиперинфляцией, таких как Венесуэла и Зимбабве.

Подобные случаи можно наблюдать в таких странах, как Зимбабве, где в одноранговых платежах в цифровых валютах произошел резкий рост.

В некоторых странах власти серьезно изучают возможности и риски, связанные с введением поддерживаемой правительством криптовалюты, как потенциальной альтернативы традиционной фиатной валюте. Центральный банк Швеции является одним из первых. Другие известные примеры включают центральные банки Сингапура, Канады, Китая и США.

Заключение

Хотя случаев гиперинфляции может показаться немного и они далеки друг от друга, очевидно, что относительно короткий период политических или социальных волнений может быстро привести к девальвации традиционных валют. Снижение спроса на единственный экспорт страны также может быть тому движущей причиной. Как только валюта обесценивается, цены стремительно начинают расти, что в итоге создает порочный круг. Несколько правительств пытались противостоять этой проблеме, печатая больше денег, но лишь одна эта мера оказалась бесполезной и только послужила дальнейшему снижению общей стоимости валюты. Также следует отметить, что по мере падения доверия к традиционной валюте, вера в криптовалюту имеет тенденцию к росту. Это может иметь серьезные последствия для будущего, и того как эти деньги будут рассматриваться в глобальном масштабе.